Asynchronicity in Programming Languages

Computers are asynchronous by design.

Asynchronous means that things can happen independently of the main program flow.

In the current consumer computers, every program runs for a specific time slot and then it stops its execution to let another program continue their execution. This thing runs in a cycle so fast that it's impossible to notice. We think our computers run many programs simultaneously, but this is an illusion (except on multiprocessor machines).

Programs internally use interrupts, a signal that's emitted to the processor to gain the attention of the system.

I won't go into the internals of this, but just keep in mind that it's normal for programs to be asynchronous and halt their execution until they need attention, allowing the computer to execute other things in the meantime. When a program is waiting for a response from the network, it cannot halt the processor until the request finishes.

Normally, programming languages are synchronous and some provide a way to manage asynchronicity in the language or through libraries. C, Java, C#, PHP, Go, Ruby, Swift, and Python are all synchronous by default. Some of them handle async by using threads, spawning a new process.

JavaScript

JavaScript is synchronous by default and is single threaded. This means that code cannot create new threads and run in parallel.

Lines of code are executed in series, one after another, for example:

const a = 1;

const b = 2;

const c = a * b;

console.log(c);

doSomething();

But JavaScript was born inside the browser, its main job, in the beginning, was to respond to user actions, like onClick, onMouseOver, onChange, onSubmit and so on. How could it do this with a synchronous programming model?

The answer was in its environment. The browser provides a way to do it by providing a set of APIs that can handle this kind of functionality.

More recently, Node.js introduced a non-blocking I/O environment to extend this concept to file access, network calls and so on.

Callbacks

You can't know when a user is going to click a button. So, you define an event handler for the click event. This event handler accepts a function, which will be called when the event is triggered:

document.getElementById('button').addEventListener('click', () => {

//item clicked

});

This is the so-called callback.

A callback is a simple function that's passed as a value to another function, and will only be executed when the event happens. We can do this because JavaScript has first-class functions, which can be assigned to variables and passed around to other functions (called higher-order functions)

It's common to wrap all your client code in a load event listener on the window object, which runs the callback function only when the page is ready:

window.addEventListener('load', () => {

//window loaded

//do what you want

});

Callbacks are used everywhere, not just in DOM events.

One common example is by using timers:

setTimeout(() => {

// runs after 2 seconds

}, 2000);

XHR requests also accept a callback, in this example by assigning a function to a property that will be called when a particular event occurs (in this case, the state of the request changes):

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = () => {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

xhr.status === 200 ? console.log(xhr.responseText) : console.error('error');

}

};

xhr.open('GET', 'https://yoursite.com');

xhr.send();

Handling errors in callbacks

How do you handle errors with callbacks? One very common strategy is to use what Node.js adopted: the first parameter in any callback function is the error object: error-first callbacks

If there is no error, the object is null. If there is an error, it contains some description of the error and other information.

fs.readFile('/file.json', (err, data) => {

if (err !== null) {

//handle error

console.log(err);

return;

}

//no errors, process data

console.log(data);

});

The problem with callbacks

Callbacks are great for simple cases!

However every callback adds a level of nesting, and when you have lots of callbacks, the code starts to be complicated very quickly:

window.addEventListener('load', () => {

document.getElementById('button').addEventListener('click', () => {

setTimeout(() => {

items.forEach((item) => {

//your code here

});

}, 2000);

});

});

This is just a simple 4-levels code, but I've seen much more levels of nesting and it's not fun.

How do we solve this?

Alternatives to callbacks

Starting with ES6, JavaScript introduced several features that help us with asynchronous code that do not involve using callbacks: Promises (ES6) and Async/Await (ES2017).

We all know that JavaScript is a *Single Threaded *language, this means, things happen one at a time. Consider the below code:

Here, the action is performed one line at a time. So, line 1 and 2 will be executed before line 3. At Line 3, we have a function call, so the actions at line 4 won't be executed until and unless the function is returned. This is called as Synchronous Programming model. These type of statements are also known as *Blocking, *as no other statement will execute before the current statement is finished. This model makes use of a stack called as "Call Stack".

What is a Call Stack?

A Stack Data Structure

A Call Stack is a data structure which keeps the record of which statement is currently being executed. We know how a stack works, which is basically *"Last In, First Out" *approach i.e. the last element pushed in will be the first to be popped out.

So, when we encounter any statement, it is pushed to the top of the stack and is executed. Once the execution is completed, it is then popped out of the stack. If one of those statement is a Function, we push it on to the top of the stack and it is popped off only when we return from the function.

Let's understand it with an example.

Output:

125

In the beginning of the execution of the code by the engine, the call stack will be empty. Then, the following will happen:

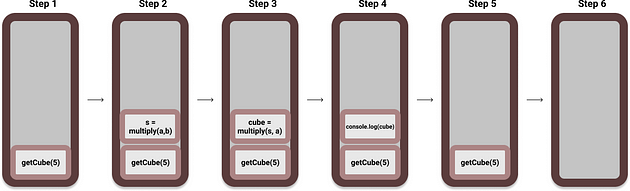

Working of the Call Stack during program execution.

Since these all are Blocking Statements, the are pushed into the stack and are popped out once they are executed. The next statement has to wait till the previous statement is popped out of the stack.

Fun Fact: The above explained process is how a stack trace is constructed. It is basically the snapshot of the stack at the time of any exception. Also, this is the same reason why the "RangeError: Maximum call stack size exceeded" error is also thrown. This happens when the number of function calls in the Call Stack exceeds the size of the stack.

To further understand the working of a Call Stack, observe the execution of the below code:

Why is having Single Thread considered a problem then?

To answer this, imagine a complex algorithm, maybe one which involves such a function which takes user's data and sends it on a network for processing. Once the data is processed then only the function returns some value and the user is allowed to proceed ahead. Keep in mind that this algorithm is running on a browser. Can you guess the problem now?

Yes, having a single thread executing this algorithm will involve *Blocking Statements. *These statements will be pushed into the Call Stack, one at a time. The next statement has to wait for the previous statement to finish to start it's own execution. So, if the Call Stack is blocked by this complex function, then the Browser will be stuck as it can't execute anything else and has to wait for the function to be popped from the call stack.

Most of the browsers will not wait for much long and will give a pop up saying that the Page is Unresponsive, asking whether you want to terminate the web page.

What is the Solution to this problem?

The solution is simple, we need to use *Asynchronous Programming model. *When any asynchronous action is started, the rest of the program continues to execute normally. Then, as soon as the asynchronous action is completed, the program is informed about it and it accesses that particular result. In short, this model allows multiple things to happen at the same time.

This is clear from the above explanation, that the rest of the code is not *"blocked" *when any asynchronous code is executed. This is the reason these statements are also known "Non-Blocking Statements".

Let's try to understand how are Non-Blocking Statements executed in JavaScript

Consider the code below,

Output:

10

20

200 (after 1 second)

How did this happen? We saw that each statement is executed one at a time using the Call Stack, and the next statement waits for the previous one to complete it's execution, right? Well, this is nothing but the magic of Asynchronous code.

As mentioned a few paragraphs above, an Asynchronous statement is *"Non-Blocking". This means, this type of statements do not block the normal execution of other statements. *This clearly points to the fact that there is actually some difference in the way the Synchronous and Asynchronous statements are processed. So what's the secret behind JavaScript's Asynchronous programming? The answer to this question is "Event Loop".

Understanding JavaScript Event Loop

If you are able to follow till now, this means you are aware about something known as a JavaScript Engine or Runtime. Most popular of them is Google's V8 engine (it is used inside Chrome, Node.js, etc). It consists of a Memory Heap and a Call Stack (Yes, the same Call Stack that we discussed above). But when you try to dig into the V8 code base and try to find things like *"DOM", "HttpRequest", *etc, you wont find them anywhere as they do not exist in V8. Then how is JavaScript able to handle Asynchronous operations? Just kind of statements are traditionally performed by Threads in languages like *Ruby *or Java.

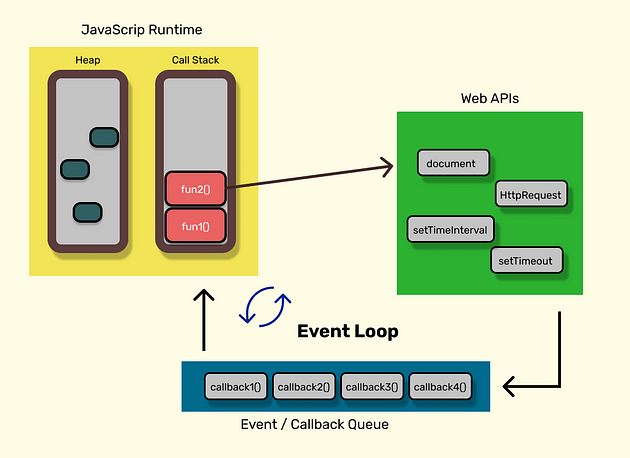

The reason is, that the browser is more than just the runtime. To support the Runtime, the browser also provides WebAPIs, which are effectively like threads but we can't access them like normal threads, instead we can make calls to them to achieve some functionality. In case of Node.js, instead of WebAPIs, we have C++ APIs where all the threading and stuff is hidden from us at C++ side. Along with WebAPIs, there is another thing involved in this process, which is called "Event (or Callback) Queue". Collectively, all these components with the help of *"Event Loop" *helps JavaScript perform asynchronous opetations. Consider the below diagram:

Event Loop in JavaScript--- https://medium.com/@aditya.shukla278

- Javascript Engine/Runtime: Javascript engines like Google V8, SpiderMonkey, Chakra etc. provide the JavaScript Runtime. It consists of two components, Call Stack and Memory Heap. The Heap is basically used to maintain object and function references which are required by call stack.

- WebAPIs: The Browser provides the APIs like setTimeout, setInterval, document etc. So, while executing the code if a statement with callback is pushed into the stack, that statement is directly popped out of the stack and then these APIs are responsible to add those callbacks into the event queue. For eg.

setTimeout(cb1, 2000)will add the callback functioncb1in event queue after the 2 seconds. - Event Queue: Event queue basically contains callback functions which are to be added back into the call stack by event loop. This is the reason they are also called as "Callback Queue".

- Event Loop: Now, the Event Queue has the callback function which is needed to be pushed back to the Call Stack, here this *Event loop *comes into picture. It is responsible to push the callbacks available in event queue to the call stack. Event loop pushes a callback function only when the call stack is empty.

That is too much of words, I bet you must be sleepy by now. Consider the below code to understand the working of the Event Loop.

Point to be noted here: Event loop will only add the callback from the event queue to the call stack when it finds the call stack empty. If JavaScript's main thread is busy executing a long running function, it would keep the callback in the event queue. That is why it is important that we make sure that the main call stack does not have long running functions which may block it, as that time browser would not be able to respond to user events as they would be stuck in event queue.

To Summarize the above topics ---

- We understood that JavaScript is a *Single Threaded *language, which basically means that the statements are executed one at a time.

- These statements block the execution of the immediate next statements until they are completed executed. Because of this reason they are also known as Blocking Statements.

- The statements are executed using a *Call Stack. *A statement which has to be executed, it is pushed into the stack, executed, and then popped out of the stack. All the nested/recurring function calls are stacked on top of each other.

- An Event loop is browser's mechanism to perform non-blocking operations by providing WebAPIs (setTimeout, setInterval, etc.) which are capable of maintaining callback references in memory.

- The callbacks are then added to event queue.

- Finally. the Event loop pushes the callback back to the *Call Stack from the Event queue *when the call stack is empty. Here the callback is executed.